Advance Regression - Ridge, Lasso, Gradient Descent

- Constrained Minimization

- Unconstrained Minimization

- Closed form

- SLR

- MLR

- Questions

- Identifying Non-Linearity in Data

- Handling Non-Linear Data

- Polynomial Regression

- Questions

- Questions

- Overfitting

- Questions

- Takeaways

- References

Constrained Minimization

Constrained minimisation is a process in which we try to optimise an objective function with respect to some variables in the presence of the constraints on the variables or the function. In our case, the objective function is a cost function.

- Ridge/Lasso Regression and SVM use Constrained Minimization

- The solution to the overall minimisation problem is the point where the error is minimum while satisfying the additional constraint.

Ridge and Lasso Regression

- Adding constraints over the weights is called regularization and ridge and lasso are two common techniques used for this purpose.

Signature of overfitting in Polynomial Regression

- The weights of the coefficients are very large

- In regularization, we combat overfitting by controlling the model's complexity, i.e. by introducing an additional term in our cost function in-order to penalize large weights. This biases our model to be simpler, where simpler is weights of smaller magnitude (or even zero). We want to make the weights smaller because complex models and overfitting are characterized by large weights.

- Adding constraints over the weights / coefficients is called regularization and it helps in resolving overfitting issue because having large weights is one of the signs off overfitting so if we put a constraint over weights, that will make sure large weights are not assigned and hence model does not overfit.

Ridge

- Constraint over sum of squared weights ( < )

- represents a region bounded by a circle in 2D space

- Ordinary least squares with L2 regularisation is known as Ridge Regression.

- In L2 regularisation, large weights are being penalized much more

- Ex:

Lasso

- Constraint over sum of absolute weights ( < )

- represents a region bounded by a square in 2D space

- Gives sparse solution

- In L1 regularization the model's parameters become sparse during optimization, i.e. it promotes a larger number of parameters w to be zero. This is because smaller weights are equally penalized as larger weights

- This sparse property is often quite useful. For example, it might help us identify which features are more important for making predictions, or it might help us reduce the size of a model (the zero values don't need to be stored).

- Ex:

Unconstrained Minimization

Unconstrained minimisation, on the other hand, is a process in which we try to optimise the objective function with respect to some variables without any constraints on those variables.

- Linear Regression and Logistic Regression use Unconstrained Minimization

- There is no explicit condition on the parameters but they are in turn calculated with the condition that the cost function needs to be minimized.

- Gradient Descent is one way of solving unconstrained minimisation

Closed form

Gradient Descent

1D Gradient Descent

Let's assume the following starting conditions:

Substituting,

In gradient descent, you start with some initial value and then gradually approach the optimal solution.

Steps of Gradient Descent

- We try to find the optimal minima by using Gradient Descent algorithm

- Choose the values of eta (learning rate) and initial theta (optimal value to be obtained)

-

Use the formula

- Continue substituting new value to old value till the value becomes similar over several iterations

In other words,

- Choose a starting point

- Beginning at , generate a sequence of iterates with respect to a cost function (f) value which has to be minimized until a solution with sufficient accuracy is found or until no further progress can be made.(inf=infinity)

2D Gradient Descent

=

For the case of Linear Regression

=

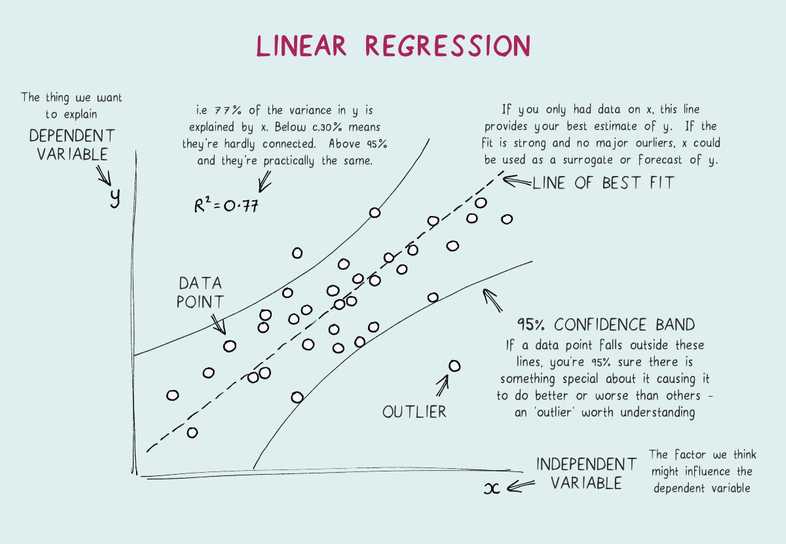

Metrics

- Overall sense of error of the model

- Smaller the RSS, closer is the model fit

RSS

Mean Square Error

Root Mean Square Error

SLR

for i = i to n,

for n observations, equations can be written as:

This can be written more efficient in matrix notation:

In more concise form:

here,

- Y: Response Vector

- X: Design matrix

- : Coefficient Vector

- : Error Vector

Benefits of Using Matrices

- Formulae become simpler, and more compact and readable.

- Code using matrices runs much faster than explicit ‘for’ loops.

- Python libraries, such as NumPy, help us build n-dimensional arrays, which occupy less memory than Python lists and computation is also faster.

SLR Equation in Matrix Form

MLR

for i = i to n,

- ,

- where k is the number of variables in the model

Matrix Notation:

Dimension:

It can still be written as:

here,

- Y: Response Vector

- X: Design matrix

- : Coefficient Vector

- : Error Vector

Residual:

Questions

How will you identify the presence of heteroscedasticity in the residuals?

- Plot residuals vs the predicted values and see of there is a consistent change in the residuals as we move from left of the x axis to the right.

How would you check for the assumptions of Linear Regression?

- Scatter Plot of residuals vs y_pred

- Histogram Plot of residuals

Identifying Non-Linearity in Data

-

For SLR

- scatter plot and check non-linear patterns

-

For MLR

- check residuals vs predictions plot for non-linearity

- residuals are scattered randomly around 0

- spread of residuals should be constant

- no outliers in the data

- If non-linearity is present, then we may need to plot each predictor against the residuals to identify which predictor is nonlinear.

Handling Non-Linear Data

- Polynomial regression

- Data Transformation

- Non-Linear Regression

- Polynomial regression and data transformation allow to use the linear regression framework to estimate model coefficients

Polynomial Regression

Substitute the variable as and as

This way, we can express non-linear data in linear regression model

The kth-order polynomial model in one variable is given by:

If and j = 1, 2, ..., k, then the model is a multiple linear regression model with k predictor variables, . Thus, polynomial regression can be considered an extension of multiple linear regression and, hence, we can use the same technique used in multiple linear regression to estimate the model coefficients for polynomial regression.

Questions

On inspection of the relationship between one predictor variable (a) and the response variable (y), you identify that the two have a cubic relationship. In the final model, which predictors will you include?

- Since this is a cubic fit, we need to include third degree of the predictor. In polynomial regression, we need to include the lower degree polynomials in the model as well. Hence, we include all three predictors as mentioned in the answer.

- Model Equation:

Data Transformation

- both response and predictors can be transformed

- One can take a log transform over data if there is sharp upward trend which then normalizes

- After transform:

- There are other transformations one can perform. Refer this article for more information.

When to do transformation

- If there is a non-linear trend in the data, the first thing to do is transform the predictor values.

- When the problem is the non-normality of error terms and/or unequal variances are the problems, then consider transforming the response variable; this can also help with non-linearity.

- When the regression function is not linear and the error terms are not normal and have unequal variances, then transform both the response and the predictor.

-

In short, generally:

- Transforming the y values helps in handling issues with the error terms and may help with the non-linearity

- Transforming the x values primarily corrects the non-linearity

Questions

What is the equation for exponential transformation?

Give Examples where Linear Regression (even with transformation) cannot be applied

After transforming the data in case of nonlinear relationship between the predictor and response variable, how do we assess whether the data transformation was appropriate?

- We assess this by checking the residual plots for any violation in assumptions.

Pit Falls of Linear Regression

Non-constant variance

Constant variance of error terms is one of the assumptions of linear regression. Unfortunately, many times, we observe non-constant error terms. As discussed earlier, as we move from left to right on the residual plots, the variances of the error terms may show a steady increase or decrease. This is also termed as heteroscedasticity.

When faced with this problem, one possible solution is to transform the response Y using a function such as log or the square root of the response value. Such a transformation results in a greater amount of shrinkage of the larger responses, leading to a reduction in heteroscedasticity.

Autocorrelation

This happens when data is collected over time and the model fails to detect any time trends. Due to this, errors in the model are correlated positively over time, such that each error point is more similar to the previous error. This is known as autocorrelation, and it can sometimes be detected by plotting the model residuals versus time. Such correlations frequently occur in the context of time series data, which consists of observations for which measurements are obtained at discrete points in time.

In order to determine whether this is the case for a given data set, we can plot the residuals from our model as a function of time. If the errors are uncorrelated, then there should be no observable pattern. However, on the other hand, if the consecutive values appear to follow each other closely, then we may want to try an autoregression model.

Multicollinearity

If two or more of the predictors are linearly related to each other when building a model, then these variables are considered multicollinear. A simple method to detect collinearity is to look at the correlation matrix of the predictors. In this correlation matrix, if we have a high absolute value for any two variables, then they can be considered highly correlated. A better method to detect multicollinearity is to calculate the variance inflation factor (VIF).

When faced with the problem of collinearity, we can try a few different approaches. One is to drop one of the problematic variables from the regression model. The other is to combine the collinear variables together into a single predictor. Regularization helps here as well.

Overfitting

When a model is too complex, it may lead to overfitting. It means the model may produce good training results but would fail to perform well on the test data. One possible solution for overfitting is to increase the amount and diversity of the training data. Another solution is regularization.

Extrapolation

Extrapolation occurs when we use a linear regression model to make predictions for predictor values that are not present in the range of data used to build the model. For instance, suppose we have built a model to predict the weight of a child given its height, which ranges from 3 to 5 feet. If we now make predictions for a child with height greater than 5 feet or less than 3 feet, then we may get incorrect predictions. The predictions are valid only within the range of values that are used for building the model. Hence, we should not extrapolate beyond the scope of the model.

Overfitting

When a model performs really well on the data that is used to train it, but does not perform well with unseen data, we know we have a problem: overfitting. Such a model will perform very well with training data and, hence, will have very low bias; but since it does not perform well with unseen data, it will show high variance.

- When Model is too complex, the bias is low, while the variance is high. It has essentially memorized the whole dataset instead of creating a general pattern from it.

- When Model is too simple, the bias is high, while the variance is low. It means that the model has not learned anything at all. This is called Underfitting. Here both the training and testing error is going to be high.

- Refer this for more details

Regularization

Regularization helps with managing model complexity by essentially shrinking the model coefficient estimates towards 0. This discourages the model from becoming too complex, thus avoiding the risk of overfitting.

For Linear Regression, Model Complexity depends on

- Magnitude of the coefficients

- Number of coefficients

In OLS,

- minimizing the cost function leads to low bias, or in other words Overfitting.

-

The coefficients obtained can be highly unstable.

- only few predictors are significantly related to target

- multicollinearity

To solve this,

- Add a penalty to cost term i.e Cost function = RSS + Penalty

- Error Function:

-

There are two common techniques which employ this method.

- Ridge:

- Lasso:

- Ridge:

When we regularize, we sacrifice a little bias in favor of a significant reduction in variance.

One sign of overfitting is extreme values of model coefficients. Hence, regularization helps as it shrinks the coefficients towards 0.

Tradeoff between Error and Regularization

- Suppose and with the most optimal is while with the most optimal is

- It follows that (1)

- and (2)

- If we combine and shuffle (1) and (2)

- Since , and , we can say that

- Hence,

- When we increase the value of λ, the error term will increase and regularisation term will decrease and the opposite will happen when we decrease the value of λ.

Ridge Regression

In OLS, we get the best coefficients by minimising the residual sum of squares (RSS). Similarly, with Ridge regression also, we estimate the model coefficients, but by minimising a different cost function. This cost function adds a penalty term to the RSS.

- Here, is the penalty term

- It has the effect of shrinking s towards zero to minimize cost

One point to keep in mind is that we need to standardise the data whenever working with Ridge regression. We have seen that regularization puts a constraint on the magnitude of the model coefficients. Then the penalty term depends upon the magnitude of each coefficient. This makes it necessary to centre or standardise the variables.

Role of Lambda

If lambda is 0, then the cost function would not contain the penalty term and there will be no shrinkage of the model coefficients. They would be the same as those from OLS. However, since lambda moves towards higher values, the shrinkage penalty increases, pushing the coefficients further towards 0, which may lead to model underfitting. Choosing an appropriate lambda becomes crucial: If it is too small, then we would not be able to solve the problem of overfitting, and with too large a lambda, we may actually end up underfitting.

Another point to note is that in OLS, we will get only one set of model coefficients when the RSS is minimised. However, in Ridge regression, for each value of lambda, we will get a different set of model coefficients.

Higher more regularization

- if is too high, it will lead to underfitting

- if is too low, it will not handle overfitting

Summary - Ridge Regression

- Ridge regression has a particular advantage over OLS when the OLS estimates have high variance, i.e., when they overfit. Regularization can significantly reduce model variance while not increasing bias much.

- The tuning parameter lambda helps us determine how much we wish to regularize the model. The higher the value of lambda, the lower the value of the model coefficients, and more is the regularization.

- Choosing the right lambda is crucial so as to reduce only the variance in the model, without compromising much on identifying the underlying patterns, i.e., the bias.

- It is important to standardise the data when working with Ridge regression.

- The model coefficients of ridge regression can shrink very close to 0 but do not become 0 and hence there is no feature selection with ridge regression. This can cause problems with interpretability of the model if the number of predictors is very large.

Lasso Regression

- Here, is the penalty term

- If is large enough, the coefficient for some of the variables will become zero. Hence it performs variable selection.

- Models generated from Lasso are generally easier to interpret than those produced by Ridge Regression

- Standardising the variable is necessary for lasso as well

- No closed form solution is possible as compared to ridge

- Gives a sparse solution i.e many of the model coefficients auomtically become exactly zero,

-

If is the best model that we end up getting, which is given as:

- , then

- where of a model is defined by the number of parameters in that are exactly equal to zero.

- Choosing correct is important. If it is too large, all coefficients will become zero.

Summary - Lasso Regression

- The behaviour of Lasso regression is similar to that of Ridge regression.

- With an increase in the value of lambda, variance reduces with a slight compromise in terms of bias.

- Lasso also pushes the model coefficients towards 0 in order to handle high variance, just like Ridge regression. But, in addition to this, Lasso also pushes some coefficients to be exactly 0 and thus performs variable selection.

- This variable selection results in models that are easier to interpret.

Generally, Lasso should perform better in situations where only a few among all the predictors that are used to build our model have a significant influence on the response variable. So, feature selection, which removes the unrelated variables, should help. But Ridge should do better when all the variables have almost the same influence on the response variable.

It is not the case that one of the techniques always performs better than the other – the choice would depend upon the data that is used for modelling.

We often have a large number of features in real-world problems, but we want the model to be able to pick up only the most useful ones (since we do not want unnecessarily complex models). Since lasso regularisation produces sparse solutions, it automatically performs feature selection.

Questions

As λ increases from 0 to infinity, what is the impact on Variance, RSS, Test Error, Ridge Coefficients, Lasso Coefficients and Bias of the model?

- Variance decreases: When λ=0, the alphas have their least square estimate values. The actual estimates heavily depend on the training data and hence variance is high. As we increase λ, alphas start decreasing and model becomes simpler. In the limiting case of λ approaching infinity, all betas reduce to zero and model predicts a constant and has no variance.

- RSS increases: Differentiating the cost function with lambda=0 gives the value of the coefficients which minimizes the RSS. Again, putting λ = infinity gives us a constant model with maximum RSS. Thus, the RSS steadily increases with the variation of lambda

- Bias increase: When λ=0, alphas have their least-square estimate values and hence have the least bias. As λ increases, alphas start reducing towards zero, the model fits less accurately to training data and hence bias increases. In the limiting case of λ approaching infinity, the model predicts a constant and hence bias is maximum.

- Test error will be high: Even though the variance will be very low, test error will be high as the model would not have captured the behaviour of the data correctly.

- Ridge will lead to some of the coefficients to be very close to 0.

- Lasso will cause some of the coefficients to be 0.

Ridge vs Lasso

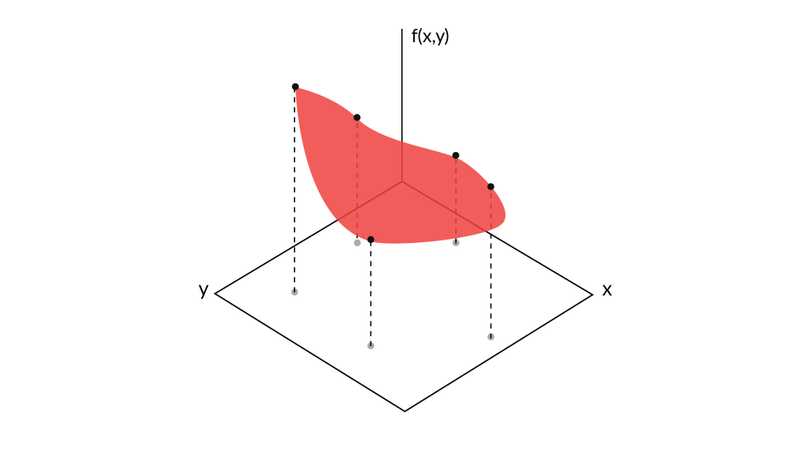

Visualizing a function

- For a function given as , a third axis, say Z is used to plot the output values of the function, and once we connect all the values, we get a surface.

Visualizing Function using Contours

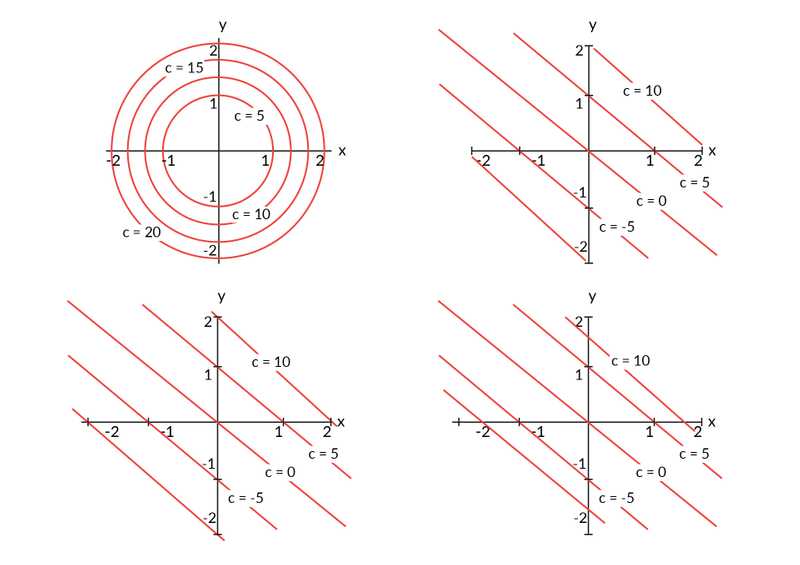

- For contours, we join all the points where the function value is the same and we end up getting a contour for the function, which is the visual representation of the function.

- No two contours can intersect, which means a function can't have two different values for a combination of x and y but two contours can meet tangentially.

Visualizing Difference between Ridge and Lasso

Observing the plots above, we see that we can get the model coefficients to become 0 only if the ellipses touch the constraint region on either the x or the y axis. Since the Ridge regression constraint is circular, without any sharp points, the ellipse will generally not touch the circular constraint region at the axis.

Hence, the coefficients can become very small but would not become 0. In the case of Lasso regression, since the diamond constraint has a corner at each axis, the ellipse would touch the constraint at any of its corners often, resulting in that coefficient becoming 0. In higher dimensions, since there will be a higher number of corners, a higher number of coefficients can become 0 at the same time.

This is the reason Lasso regression can perform feature selection.

Takeaways

- If hyperparameter lambda is high, it will lead to underfitting, while if it is low, it will not handle overfitting.

- Ridge regression does not make the coefficient zero, while lasso regression does.

- Both ridge and lasso have the same idea of adding a penalty to the cost function based on the weight of the coefficients. in ridge, the penalty is on the sum of squares of the coefficients, while in lasso it is on the sum of the absolute value of the coefficients.