Model Free Methods

- Preface

- Monte-Carlo Methods * Points to consider

- Monte-Carlo Prediction

- Monte-Carlo Control

- Summary

- References

Preface

In most real-world scenarios, the model is not available. You have to implicitly infer the model from the observations. Methods designed to solve these scenarios are called model-free methods. Examples of such model-free environments are self-driving space, games such as Chess, Go, etc.

Monte-Carlo Methods

Monte-Carlo method is based on the concept of the law of large numbers.

The law of large numbers says that if you take a very large sample, it will give similar results as to what you would get if you would have known the actual distribution of the samples.

The expected value of a random variable is the weighted average over the probabilistic distribution values. It can also be thought of as the average (or mean) of a (~infinitely) large enough sample drawn from the same distribution.

such that

Let's first rearrange the q-value function a bit.

where ;

As you know that where is a probability, such that

Hence, the Q-function can be written as the expected value of total rewards over model distribution:

Say, you run the episodes an infinite number of times and calculate the rewards earned every time a (state, action) pair is visited. Then take the average of these values. The average value will give you an estimate of the actual expected state-action value for that (state, action) pair.

The Monte-Carlo methods require only knowledge base (history/past experiences)—sample sequences of (states, actions and rewards) from the interaction with the environment, and no actual model of the environment.

Points to consider

- In model-free methods, the random variable X is the estimated total reward ()

- For a large number of samples, average reward equals expected reward.

Monte-Carlo Prediction

Prediction and control are two integral steps to solve any Reinforcement learning problem.

- Prediction - evaluating the value function/policy

- Control - improving the policy basis the state-value function estimates

The Monte-Carlo prediction problem is to estimate i.e. the expected total reward the agent can get after taking an action from state .

- For estimating this, you need to run multiple episodes

- Track the total reward that you get in every episode corresponding to this (s, a) pair

- The stimated action-value is the given by

The most important thing to ensure is that, while following the policy , each state-action pair should be visited enough number of times to get a true estimate of . For this, you need to keep a condition known as the exploring starts. It states that every state-action pair should have a non-zero probability of being the starting pair.

Model-free methods work directly with the q-function rather than state-value functions. The agent needs to estimate the value of each action to find an optimal policy.

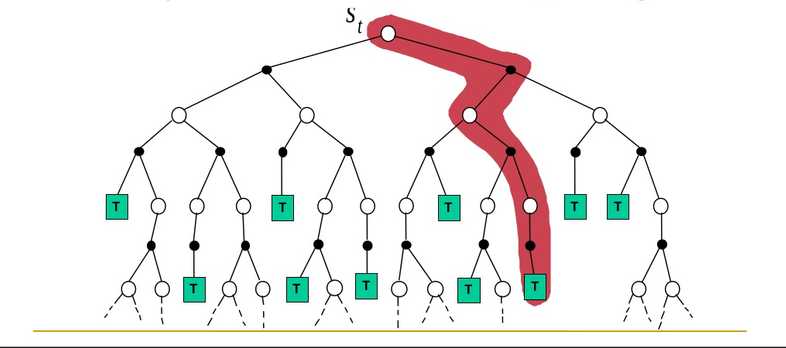

Reason for exploring starts: To get an estimate of the state (s, a), you run multiple episodes starting from the same state-action pair (s, a), so you’ll need to start multiple episodes from (s, a), but what you need to ensure is that once the agent reaches s', it takes all possible actions from s' in various episodes (and not just take the ones that are more probable according to the current policy). Because if that happens, then all the (the total rewards in various episodes) will basically be the same.

Monte-Carlo Control

We know how to evaluate Q-function for a given policy. Now, you can use these q-values for the control problem.

Recall that the control problem is to improve the existing policy in order to find an optimal policy. Let's see how you can do it.

Policy improvement is done by constructing an improved policy as the -greedy maximisation with respect to . So, is:

where |A(s)| is the action space, i.e. total possible actions in any given state.

Exploration vs Exploitation

- Exploration refers to the scenario where you do not follow the actions suggested by the policy. Instead, you go and explore some other actions.

- Exploitation refers to the scenario where you religiously follow the actions suggested by the policy.

Let's understand what it means to have a -greedy policy.

is a hyperparameter that controls the tradeoff between exploration and exploitation.

- If is too small, then actions are biased to be more greedy

- If is too large, then actions explore more

It is important too choose carefully. To ensure that the improved policy is better than , you fall back to Policy Improvement Theorem which says that:

Off Policy

You learnt that the control problem seeks the best action values for the agent to behave optimally.

However, the agent has to behave non-optimally in order to explore other actions (i.e. the actions that are not given by the policy), to find better action than already existing one.

How does the agent learn the optimal policy while it is continuing to explore?

A way to handle the dilemma of exploring and exploitation is by using two policies:

- Target Policy: The policy that is learnt by the agent and that becomes the optimal policy

- Behaviour Policy: The policy that is used to generate the episodes and is more exploratory in nature

This is called off-policy because the agent is learning from data 'off' the behavior policy.

In another case, if the (optimal) policy learnt and the policy that is used to generate episodes are the same, it is called on-policy learning.

Let's say that you are trying to estimate , and is your target policy. But the episodes are generated by some other behaviour policy where . If the action generated under policy is not getting explored under , then you'll never have true estimates of . Thus, it is important to ensure that every action taken under is also taken, at least occasionally, under .

How do you ensure that every action taken under is also taken, at least occasionally, under .

Importance Sampling

Importance sampling is a technique that is used to ensure that the state-actions pairs produced by the target policy are also explored by behaviour policy.

The sample episodes are produced by behaviour policy but you want to learn a target policy.

Thus it is important to measure how important/similar the samples generated are to samples that the target policy may have made. Importance sampling is one way of sampling from a weighted distribution which favours these "important" samples.

Temporal Difference

There are some inherent issues with Monte-Carlo. To start with, you need to wait until the end of the episode to update the expected rewards for a state-action pair.

Similar to Monte-Carlo, Temporal Difference (TD) methods also learn directly from experience without an explicit model of the environment.

The major difference between these two methods is:

- In Monte Carlo methods, you need to wait until the end of the episode and then update the q-value

- In TD methods, you can update the value after every few time steps. This update mechanism is often advantageous since it gives the agent early signals if some of the eventual states are disastrous, and so the agent avoids that path altogether.

Let's understand this through an example.

Say there are two agents in a chemical plant. One is learning using Monte-Carlo while the other is learning using TD. Each day is a new episode for them. One day, they both changed the similar valves (action). The pressure in one of the tube increased too much and the yield of the product started decreasing (the reward started becoming negative). The TD agent will update the q-value of this action (i.e. reduce it immediately) and will instead take some other action that will increase the future rewards. On the other hand, the Monte-Carlo agent will continue taking actions according to its policy. The pressure could increase beyond a threshold level leading to a blast. After this episode, the MC agent would realise that the action (of turning that valve) was quite bad and update the policy accordingly, though the TD agent cleverly avoided all the trouble altogether.

Temporal Difference Algorithm

Let's understand the TD algorithm using a small example:

Say you played the game of Chess 10,000 times (episodes) over a period of 5 years. You have learnt that when you take a particular action from some board position, you always end up getting a high reward - the q(s, a) is 100 for that state-action pair. Today, when you played the game, you got a total reward of 70 (starting from the same state-action pair). How will you update the value of q(s, a)? You cannot directly make it 70 as you can't ignore the learning of 5 years. Also, intuitively, you know that the updated value should be lesser than 100 (since the latest reward of 70 is lesser than 100). So you'll update the q-value incrementally in the direction of the new, latest learning.

Typically, any TD algorithm could be written as:

new q-value = old q-value + (current value - old q-value)

Now, is the learning rate that decides how much importance you give to your current value.

- If is too low, it means that you value the incremental learning less

- If is too high, it means that you value the incremental learning more

TD update equation relies on a similar idea. There are many different versions of TD update. The only difference in all updates is the calculation of current value.

Q-Learning

In Q-learning, you do max-update. After taking action $srs's'$, you take the most greedy action, i.e., the action with the highest q-value.

So, q-value function update becomes:

Here, is the TD Error. It is the difference between current value obtained - current estimate of q-value.

Q-learning learns the optimal policy 'relentlessly' because the estimates of q-values are updated based on the q-value of the next state-action pair assuming the greediest action will be taken subsequently.

If there is a risk of a large negative reward close to the optimal path, Q-learning will tend to trigger that reward while exploring. And in practice, if the mistakes are costly, you don't want Q-learning to explore more of these negative rewards. You will want something more conservative.

There are other approaches like SARSA, Double Q-learning, which are more conservative and avoid high risk.

Q-Learning Pseudocode

The learned action-value function, Q, directly approximates - the optimal action-value function, independent of the policy being followed. After every step, it updates the q-value of each (state-action) pair by greedily taking an action that has the maximum q-value.

- Initialization: Q(s, a)

-

Repeat

- A ~ -greedy at s w.r.t Q(s,a)

- Observe state and after taking action from

- set s as s'

Summary

In this blog, you learnt two different kinds of model-free learning methods:

- Monte-Carlo

- Temporal-difference (TD) You learnt how these can be applied to the reinforcement learning problem. Similar to DP, the problem was divided into a prediction problem and a control problem.

Monte Carlo (MC) methods learn value functions and optimal policies directly from the interaction with the environment. They average out the rewards earned from different episodes to estimate the action-value functions and use these action-value functions to improve the policy (-greedily).

is the hyperparameter that balances the trade-off between exploration and exploitation. Lower the value, lower is the exploration.

Then you learnt about off-policy methods and importance sampling. These methods deal with two kinds of policies: behaviour policy and target policy. And importance sampling ensures that important samples (important both for target and behaviour policy) are sampled more often than others.

Then, you learn about TD methods and in particular, Q-Learning. In TD methods, you can update the value after every time step. And, in practice, this update can be very advantageous when some of the states are extremely disastrous.

Q-learning directly learns the optimal policy, because the estimate of q-value is updated basis the estimate from the maximum estimate of possible next actions, regardless of which action you took.