Inferential Statistics

Purpose of Inferential Statistics

From a small dataset, we have to figure out information such that it applies to the whole population.

We will be able to estimate population data from sample data but not find the exact values.

We can make reasonable assumptions with limited level of certainty.

Expected Value

Expected Value is the average value that any random variable X will take, given it's probability of occurrence.

EV(x) = x1 * P(X=x1) + x2 * P(x=x2) + x3 * P(x=x3) + ... + xn * P(x=xn)

In Casinos, why does the house always win?

Answer: House always wins because Casinos have an expected value which is negative. This way, in the long run, even though some players might win large sums of money, the losers collective will lose a lot more money, eventually making the house win in terms of total cash flow.

Probability Distribution

It is the mathematical function that gives the probabilities of occurrence of different possible outcomes for an experiment.

It is a mathematical description of a random phenomenon in terms of its sample space and the probabilities of events.

The probabilities of occurrence of any random variable X taking any of the outcomes from the sample space

The goals of inference

- Estimate and quantify the uncertainty of an estimate of a population quantity (the proportion of people who will vote for a candidate).

- Determine whether a population quantity is a benchmark value (“is the treatment effective?”).

- Infer a mechanistic relationship when quantities are measured with noise (“What is the slope for Hooke's law?”)

- Determine the impact of a policy? (“If we reduce pollution levels, will asthma rates decline?”)

- Talk about the probability that something occurs.

Concerns

- Is the sample representative of the population that we'd like to draw inferences about?

- Are there known and observed, known and unobserved or unknown and unobserved variables that contaminate our conclusions?

- Is there systematic bias created by missing data or the design or conduct of the study?

- What randomness exists in the data and how do we use or adjust for it? Here randomness can either be explicit via randomization or random sampling, or implicit as the aggregation of many complex unknown processes.

- Are we trying to estimate an underlying mechanistic model of phenomena under study?

Takeaways

- Inferential statistics is a field where you have to determine the value for the whole population given some sample data (small dataset). Using statistics, we can give a reasonable estimate but not an exact answer. This is why, for such problems, we use probability

- Probability distribution graphs are a much better way to visualize and understand the probabilities that a random variable X can take

- We should define the random variable X to be directly linked to the problem we are trying to solve or giving an estimate about

Types of Distributions

Binomial Distribution

Conditions for Binomial distribution

- Total number of trials is fixed at n

- Each trial is binary i.e. has only two possible outcomes - success or failure

- Probability of success is same in all trails, denoted by p

- Formula: P(X=r) = P(Getting r successes in n trials) = nCr(p)r(1-p)n-r

Examples

| SNo | Binomial Distribution Applicable | Binomial Distribution Not Applicable |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Tossing a coin 20 times to see how many tails occur | Tossing a coin until a heads occurs |

| 2. | Asking 200 randomly selected people if they are older than 21 or not | Asking 200 randomly selected people how old they are |

| 3. | Drawing 4 red balls from a bag, putting each ball back after drawing it | Drawing 4 red balls from a bag, not putting each ball back after drawing it |

Explanation

If you toss a coin 20 times to see how many tails occur, you are following all the conditions required for a binomial distribution. The total number of trials is fixed (20), and you can only have two outcomes, i.e. a tails or a heads. The probability of getting a tails is equal to 0.5 each time you toss the coin.

In a way, this is similar to drawing 20 balls out of a bag, replacing each ball after drawing it, and seeing how many of the balls are red. Here, the probability of getting a red ball in one trial is 0.5.

When you toss a coin until a heads occurs, the total number of trials is not fixed. This is similar to taking out balls from the bag repeatedly until you draw a red ball. You can still find the probability of getting a heads in 1 trial, in 2 trials, in 3 trials etc. and so on, but you cannot use binomial distribution to find that probability.

In the second example, where binomial distribution is not applicable, the experiment does not have only two outcomes, but many. It is similar to taking out balls from a bag that contains red, blue, black, orange, and other colours of balls. The probability distribution for this experiment cannot be made using binomial distribution.

In the final example, the probability of the trials is not equal to each other. For example, the probability of drawing a red ball in the first trial is 3/5. Now, in the second trial, the probability of drawing a red ball would be equal to 2/4, not 3/5, as the red ball taken out in the first trial was not put back. Hence, the probability of getting the combination Red-Red-Red-Blue, for example, would be 3/5 * 2/4 * 1/3 * 2/2, which is not the value we got while deriving binomial distribution (3/5 * 3/5 * 3/5 * 2/5). Again, you cannot use binomial distribution to find the probability in this case.

In other words, binomial distribution is applicable in situations where there are a fixed number of yes or no questions, with the probability of a yes or a no remaining the same in all the questions.

Poisson Distribution

Attributes of a Poisson Experiment

A Poisson experiment is a statistical experiment that has the following properties:

- The experiment results in outcomes that can be classified as successes or failures.

- The average number of successes (μ) that occurs in a specified region is known.

- The probability that a success will occur is proportional to the size of the region.

- The probability that a success will occur in an extremely small region is virtually zero.

Note that the specified region could take many forms. For instance, it could be a length, an area, a volume, a period of time, etc.

Notation

The following notation is helpful, when we talk about the Poisson distribution.

e: A constant equal to approximately 2.71828. (Actually, e is the base of the natural logarithm system.)

μ: The mean number of successes that occur in a specified region.

x: The actual number of successes that occur in a specified region.

P(x; μ): The Poisson probability that exactly x successes occur in a Poisson experiment, when the mean number of successes is μ.

Poisson Distribution

A Poisson random variable is the number of successes that result from a Poisson experiment. The probability distribution of a Poisson random variable is called a Poisson distribution.

Formula

P(x, µ) = e-µµx/x!

Negative Binomial Distribution

- Also called Pascal Distribution

-

There are 3 ways on defining Negative Binomial Distribution, hence we should ask for clarification when someone uses that term

- Number of trials to produce r successes in a negative binomial experiment

- Number of successes before binomial experiment results in k failures

- Number of failures before binomial experiment results in r successes

Why is it called Negative Binomial Distribution?

When you hear the term negative, you might think that a positive distribution is flipped over the x-axis, making it negative. However, the “negative” part of negative binomial actually stems from the fact that one facet of the binomial distribution is reversed: in a binomial experiment, you count the number of Successes in a fixed number of trials; in the above example, you’re counting how many aces you draw. In a negative binomial experiment, you’re counting the Failures, or how many cards it takes you to pick two aces.

Notation

The following notation is helpful, when we talk about negative binomial probability.

x: The number of trials required to produce r successes in a negative binomial experiment.

r: The number of successes in the negative binomial experiment.

P: The probability of success on an individual trial.

Q: The probability of failure on an individual trial. (This is equal to 1 - P.)

b*(x; r, P): Negative binomial probability - the probability that an x-trial negative binomial experiment results in the rth success on the xth trial, when the probability of success on an individual trial is P.

nCr: The number of combinations of n things, taken r at a time.

n!: The factorial of n (also known as n factorial).

Example

Suppose we flip a coin repeatedly and count the number of heads (successes). If we continue flipping the coin until it has landed 2 times on heads, we are conducting a negative binomial experiment. The negative binomial random variable is the number of coin flips required to achieve 2 heads. In this example, the number of coin flips is a random variable that can take on any integer value between 2 and plus infinity. The negative binomial probability distribution for this example is presented below.

| Number of coin flips | Probability |

|---|---|

| 2 | 0.25 |

| 3 | 0.25 |

| 4 | 0.1875 |

| 5 | 0.125 |

| 6 | 0.078125 |

| 7 or more | 0.109375 |

Negative Binomial Probability

The negative binomial probability refers to the probability that a negative binomial experiment results in r - 1 successes after trial x - 1 and r successes after trial x. For example, in the above table, we see that the negative binomial probability of getting the second head on the sixth flip of the coin is 0.078125.

Given x, r, and P, we can compute the negative binomial probability based on the following formula:

b(x;r, P) = x-1Cr-1Pr(1-P)x-r

The Mean of the Negative Binomial Distribution

If we define the mean of the negative binomial distribution as the average number of trials required to produce r successes, then the mean is equal to:

μ = r / P

where,

μis the mean number of trials,ris the number of successes, andPis the probability of a success on any given trial.

Geometric Distribution

The geometric distribution represents the number of failures before you get a success in a series of Bernoulli trials.

Note: Special case of Negative Binomial Distribution, where 'r' i.e. number of successes is 1

Assumptions for the Geometric Distribution

- There are two possible outcomes for each trial (success or failure).

- The trials are independent.

- The probability of success is the same for each trial.

Formula

P(x) = (1 − p)x-1p

Cumulative Probability

F(x) = P(X<=x) E.g F(1) = P(X<=1) = P(X=0) + P(X=1) Last value of cumulative probability should always be 1

Summary: Discrete Probability Distributions

- We started with learning how to find probability without experiment, using basic concepts such as the addition and the multiplication rule of probability.

Takeaways

-

Binomial Distributions have the following conditions

- total number of trials is fixed

- each trial is binary (2 outcomes - success/failure)

- probability of success is same in all trials

- Formula: nCr(p)r(1-p)n-r

- There are other distributions such as Poisson, negative binomial and geometric, each with their own set of conditions, use cases and formulas. Negative binomial distribution is different from the regular one such that we count the number of failures before success.

- Cumulative probability is defined as F(x) = P(X<=x) i.e. sum of all probabilities up to & including P(x).

Question: Suppose you take 10 random pasta packets from the market and get it tested for the amount of lead. It just so happens that you have picked out packets from a very defective batch, and there is a 5% probability that any pasta packet you select is going to be defective.

Answer:

It is given that 5% of all packets are defective. We can assume that choosing a packet is a bernoulli trial. Using binomial distribution, p = 0.05 1-p = 0.95 10C2 = 45

P(X=2) = (10C2 * p^2 * (1-p)(10-2))100 = 7.46%

What is the probability that, after testing these 10 packets, not more than 2 packets would turn out to be defective?

P(X<=2) = (P(X=0) + P(X=1) + P(X=2))

WHat is the Expected Value of X?

Question:

Suppose a new cancer treatment has been discovered, claiming to increase the one year survival rate for pancreatic cancer to 40%. In other words, the probability that a patient suffering from pancreatic cancer would survive for at least one year after receiving this treatment is 40%.

Suppose a hospital is planning to use this treatment for its pancreatic cancer patients.

The hospital has a total of 10 patients suffering from pancreatic cancer. What is the probability that exactly 4 of these patients would survive the first year after receiving this treatment?

Answer: There are a total of 10 patients and the probability of surviving the first year is 40%, or 0.4 for each of them. Hence, the probability of 4 patients surviving is given by or

What is the probability that the number of patients that survive the first year after receiving the treatment would not be more than 2?

Let’s define X as the number of patients that will survive the first year after treatment. Now, according to the question, you have to find the probability of that number being less than or equal to 2, i.e. or

Continous Probability Distributions

What happens when we talk about the probability of continuous random variables, such as time, weight etc.?

It is advisable to use CDF & PDF when talking about continuous random variables, and not the bar chart distribution that we use for discrete variables.

-

A CDF, or a cumulative distribution function, is a distribution which plots the cumulative probability of X against X.

- It is monotonically non decreasing in nature

- A PDF, or Probability Density Function, however, is a function in which the area under the curve, gives you the cumulative probability.

For discrete variables, the cumulative probability does not change very frequently. In the discrete example, we only care about what the probability is for 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4. This is because the cumulative probability will not change between, say, 3 and 3.999999. For all values between these two, the cumulative probability is equal to 0.8704.

However, for the continuous variable, i.e. the daily commute time, you have a different cumulative probability value for every value of X. For example, the value of cumulative probability at 21 will be different from its value at 21.1, which will again be different from the one at 21.2 and so on. Hence, you would show its cumulative probability as a continuous curve, not a bar chart.

A commonly observed type of distribution among continuous variables is the uniform distribution. For a continuous random variable following a uniform distribution, the value of probability density is equal for all possible values.

Hence, generally, PDFs are used more commonly than CDFs.

- it is much easier to see patterns in PDFs as compared to CDFs.

- The PDF clearly shows uniformity, as the probability density’s value remains constant for all possible values. However, the CDF does not show any trends that help you identify quickly that the variable is uniformly distributed.

- it is clear that the symmetrical nature of the variable is much more apparent in the PDF than in the CDF.

Question

Cumulative Probability of Continuous Variables

Suppose you work at a sports analysis company and you want to analyse the effect a bowler’s height has on his/her performance. So, you create a list of all 5 wicket hauls in the last decade. Based on this data, they created a cumulative probability distribution for X, where X = height of the bowler who took the 5 wicket haul.

Now, based on the data, you conclude that the cumulative probability, F(175.3 cm) = 0.3. In this case, which of the following statements is correct?

- P(X<175.3 cm) = 0.3

- P(X=175.3 cm) = 0

Answer: Both 1 & 2 are correct You can say that P(X ≤ 175.3 cm) = P(X < 175.3 cm) + P(X = 175.3 cm). Now, since X is a continuous variable, you know that the probability of getting an exact value is zero. Hence, P(X=175.3 cm) = 0, which means that P(X ≤ 175.3 cm = P(X < 175.3 cm) + 0.

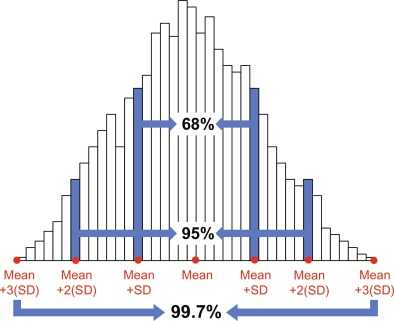

Normal Distribution

- PDF is symmetrical around mean, median & mode (1, 2, 3 rule)

- to µ + σ = 68%

- to µ + 2 σ = 95.4%

- to µ + 3 σ = 99.7%

| PMF | Mean | Variance |

|---|---|---|

| µ |

Example: This is actually like saying that, if you buy a loaf of bread everyday and measure it, then - (mean weight = 100 g, standard deviation = 1 g)

For 5 days every week, the weight of the loaf you bought that day will be within 99 g (100-1) and 101 g (100+1).

For 20 days every 3 weeks, the weight of the loaf you bought that day will be within 98 g (100-2) and 102 g (100+2).

For 364 days every year, the weight of the loaf you bought that day will be within 97 g (100-3) and 103 g (100+3).

A lot of naturally occurring variables are normally distributed. For example, the heights of a group of adult men would be normally distributed.

Uniform Distribution

| PMF | Mean | Variance |

|---|---|---|

| for x in [a, b] | ||

| 0 otherwise |

Question: Probability of Normal Random Variables

Q: Let's say that you need to find the cumulative probability for a random variable X which is normally distributed. You do not know what the value of X is or, for that matter, what the value of µ and σ is. You only know that X = µ + σ. Can you find the cumulative probability, i.e. the probability of the variable being less than µ + σ?

- Yes, probability that variable is less µ + σ is 84% by 1, 2, 3 rule

Z Score - Standard Normal Distribution

- (X=µ)/σ

- X => random variable

P(-2 < Z < 2) = P (µ - 2σ < X < µ + 2σ) = 95% P(-2 < Z < 3) = P (µ - 2σ < X < µ + 3σ) = 97.35% P(Z < 1) = P (µ + σ) = 84%

Z Table

- P(Z<=2) = .7517 (from Z table)

Question: Employee Commute time

What is the probability that an employee has a daily commute time between 25.2 and 44.8? The employee time is normally distributed, with mean (μ) = 35 and standard deviation (σ) = 5.

Question

What is the probability of a normally distributed random variable lying within 1.65 standard deviations of the mean?

Answer

You have to find the probability of the variable lying between μ-1.65σ and μ+1.65σ. i.e. P(μ-1.65σ < X < μ+1.65σ). In terms of Z, this becomes P(-1.65 < Z < +1.65). This would be equal to P(1.65) - P(-1.65) = 0.95 - 0.05 = 0.90.

As you can see, the value of σ is an indicator of how wide the graph is. This will be true for any graph, not just the normal distribution. A low value of σ means that the graph is narrow, while a high value implies that the graph is wider. This will happen because the wider graph will clearly have more values away from the mean, resulting in a high standard deviation.

Summary: Continuous Probability Distributions

-

for a continuous random variable, the probability of getting an exact value is very low, almost zero. Hence, when talking about the probability of continuous random variables, you can only talk in terms of intervals.

- For example, for a particular company, the probability of an employee’s commute time being exactly equal to 35 minutes was zero, but the probability of an employee having a commute time between 35 and 40 minutes was 0.2.

- Hence, for continuous random variables, probability density functions (PDFs) and cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) are used, instead of the bar chart type of distribution used for the probability of discrete random variables. These functions are preferred because they talk about probability in terms of intervals.

-

The major difference between a PDF and a CDF is that in a CDF, you can find the cumulative probability directly by checking the value at x. However, for a PDF, you need to find the area under the curve between the lowest value and x to find the cumulative probability.

- PDFs are still more commonly used, mainly because it is very easy to see patterns in them. For example, for a uniformly distributed variable

-

The normal distribution: it is symmetric and its mean, median and mode lie at the centre.

-

Z Score: To find the probability, you do not need to know the value of the mean or the standard deviation — it is enough to know the number of standard deviations away from the mean your random variable is. That is given by: This is called the Z score, or the standard normal variable.- Calcuating Z value without table: F(Z) = 1/√2π ∫(−∞ to Z)e−t2/2dt

Takeaways

- Continuous variables are different from discrete variables. They can take a range of values. This implies that for any discrete value in a Continuous distribution, the probability of it's occurrence is very close to 0. Hence, we always talk in terms of range of values.

- Probability Density Function (PDF) are more descriptive visually than CDFs.

- Normal distributions are a common case of continuous random variables. They occur in nature very frequently. The mean, median & mode all lie at the center.

- Converting normally distributed X to Z distribution is useful for finding probabilities with respect to σ values.

Practice Question

Q1: The regulatory authority selects a random tablet from Batch Z2. Based on previous knowledge, you know that Batch Z2 has a mean paracetamol level of 510 mg, and its standard deviation is 20 mg. What is the probability that the tablet that has been selected by the authority has a paracetamol level below 550 mg?

- Let's define X as the amount of paracetamol in the selected tablet.

-

Now, X is a normally distributed random variable,

- with mean μ = 510 mg and

- standard deviation σ = 20 mg.

-

Now, to find the probability of X being less than 550, i.e. P(X<550).

- Converting this to Z, you get P(X<550) = P(Z<{550-510}/20) = P(Z<2) = 0.977, or 97.7%.

Q2: Now, the company’s QC (Quality Control) department comes and selects a tablet at random from Batch Z2. It is interested in finding if the paracetamol level is above 450 mg or not. What is the probability that the tablet selected by QC has a paracetamol level above 450 mg?

- Let’s define X as the amount of paracetamol in the selected tablet.

-

Now, X is a normally distributed random variable,

- with mean μ = 510 mg and

- standard deviation σ = 20 mg.

-

Now, to find the probability of X being more than 450, i.e. P(X>450).

- Converting this to Z, we get P(X>450) = P(Z>{450-510}/20) = P(Z>-3) = 1 - P(Z<-3) = 0.9987, or 99.87%.

Q3: Now, let’s say that QC decides to sample one more tablet. This time, it selects a tablet from Batch Y4. Based on previous knowledge, we know that Batch Y4 has a mean paracetamol level of 505 mg, and its standard deviation is 25 mg. This time, QC wants to check both the upper limit and the lower limit for the paracetamol level. What is the probability that the tablet selected by QC has a paracetamol level between 450 mg and 550 mg?

- Let’s define X as the amount of paracetamol in the selected tablet.

-

Now, X is a normally distributed random variable,

- with mean μ = 505 mg and

- standard deviation σ = 25 mg.

-

Now, to find the probability of X being more than 450 and less than 550, i.e. P(450 < X < 550).

- Converting this to Z, we get P(450 < X < 550) = P({450-505}/25 < Z < {550-505}/25) = P(-2.2 < Z < 1.8) = P(Z < 1.8) - P(Z < -2.2) = 0.9641 - 0.0139 = 0.9502, or 95%.

References

- https://towardsdatascience.com/bean-machine-and-the-central-limit-theorem-8b0b23d6e887

- https://leanpub.com/LittleInferenceBook/read

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6YDHBFVIvIs - normal distribution - galton board experiment

- https://www.khanacademy.org/math/ap-statistics/random-variables-ap/binomial-random-variable/e/identifying-binomial-variables

- https://stattrek.com/probability-distributions/poisson.aspx

- https://www.statisticshowto.com/probability-density-function/

- https://stattrek.com/probability-distributions/negative-binomial.aspx

- https://www.statisticshowto.com/negative-binomial-experiment/

- https://www.khanacademy.org/math/ap-statistics/random-variables-ap/binomial-random-variable/e/identifying-binomial-variables

- https://www.math.arizona.edu/~rsims/ma464/standardnormaltable.pdf

- https://online.stat.psu.edu/stat414/lesson/15/15.1 - exponential

- https://online.stat.psu.edu/stat414/lesson/15/15.4 - gamma

- https://online.stat.psu.edu/stat414/lesson/15/15.8 - chi-squared